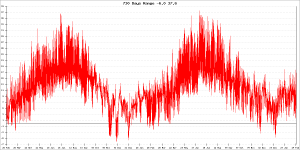

The graph is two years of temperature data here on the farm. Much like the hive scale, temperature is measured every 5 minutes and stored in a database from which we plot the graphs. Click on the graph to see a much larger version. I watched a show on one of the science oriented tv channels a couple years ago, and they had some very interesting insight. The show is called ‘orbit’, it’s a 4 part series where 2 young women travel around the world and show various major weather events that happen consistently year over year, then they proceed to explain why, it’s all to do with the tilt of the earth and our orbit around the sun, which in turn changes the amount of heating various parts of the earth get during various parts of the year. One of those ‘regularly scheduled’ events was fascinating, a waterfall in the northwest territories that freezes over. It’s a north flowing river, the fall is near Hay River, and the ice goes out in that fall in the same week every year. The reason for that, southern parts of the river start warming earlier in the season, and eventually the backlog of water is enough to start pushing the ice up to the fall, and it reaches a breaking point where you see a huge amount of ice give way and start cascading over that waterfall. As the days get longer in the south, there is more daytime heating, less night time cooling, and eventually that tipping point is reached. Timing of the ice letting go on the waterfall is driven by the length of day farther south, and it’s very consistent year over year.

We see a similar consistency here when I look at two years of temperature data collected on our property here at Rozehaven. Overnight low temps consistently dip down below 5C until we hit the 3rd week of May. But in around May 15, it’s like somebody hit the big light switch in the sky, and the overnight lows climb dramatically at that point. This becomes a very important time for using small splits as a swarm deterrent strategy. I like to use 2 or 3 frame splits for mating nucs when we start raising our replacement queens, but the data shows me, if I make those units up before May 15, they will have a high risk of chilling brood, which will set the nucs back so far they may not be viable anymore.

The other part of this equation then is the honey flows. Scale data shows us, to maximize our honey crop, we need maximum bee populations in the hives by May 1, and we want to keep those populations large thru the month of May and into June, without swarms coming out of the hives. This is the tricky part, because we are working against the bees natural instincts of trying to throw off a reproductive swarm during the spring flow. The easiest way to apply a strong swarm deterrent here on Vancouver Island, is to split hives in mid to late April, they have grown substantially by that time, and a split will set them back enough to deter swarming.

But, lets take a good hard look at the anatomy of the basic walk-away split and how that works in terms of timing for our honey flow. If we split a hive with a simple two box walk away split in late April, we end up with two halves. The donor half (box A) is now a single box, with a laying queen. They have roughly half the population and half the brood. Over the next 3 weeks that brood will all emerge, and the population will recover somewhat by mid May. The queenless half will start raising an emergency queen, and by mid May they will be in a situation of no brood left, it’s all emerged, with a queen just starting to lay. This is the time when our honey flow begins in earnest, so box A will have a reasonable, but not great population for producing honey, they will be capable of filling a super over the flow. In our second box, box B, 3 weeks after the split they have a freshly emerged queen, no brood, and a honey flow beginning. Over the next 3 weeks of flow, population is on the decline, and what bees are left need to be feeding brood, so we have less and less to forage during the heavy flow period. 3 weeks after the queen starts laying, they finally have brood emerging and the population has reached it’s low point and starting to recover, just in time for the honey flow to be tapering off. The end result of the exercise, one mediocre hive producing a box of honey, and one weak hive that will likely need support later in the season when it gets hot and dry. This ofc assumes all goes well in box A, and they just carry on after the split continuing to raise brood and expand the population. But that’s not been my experience in a walk away split. My experience is, the bees in the queenright half realize something drastic has happened, and proceed to do what bees do in that situation, they immediately start supercedure. There is a way to avoid the long and slow population decline in the queenless half of the walk away split, and that is to introduce a mated queen at the time of the split. But, if you look at the timing I mentioned above, in late April we will not have our own fresh queens to introduce, so, the only option is to purchase an imported queen for introduction into the queenless half of the split. If we do that, then both halves of the split will carry down the path mentioned above for box A, they both have a laying queen.

This is why I am not a fan of early splits as a swarm deterrent, the net result is two weaker colonies which will produce a small harvest at best, and in the worst case, no harvest at all from the spring flow we have at the lower elevations. Many of our club members have over time realized, the ‘no harvest at all’ case seems to be more predominant than the small harvest case when you use April splits as a swarm deterrent. This math changes dramatically if your focus for honey is targetting the later fireweed flow at higher elevations. If your target for honey is the fireweed, that split in April with a new introduced queen in the second half, should build well over the spring flow at lower elevations, and give you two strong hives to take up into the mountains chasing fireweed honey. That is a completely different strategy than we are using here, our target for honey flow it the spring flow here on our property. We dont have enough colonies to justify the work and expense of building an outyard in a logged patch full of fireweed. Instead, we participate in operation of a community yard set up by the local bee club, and just take a few of our colonies to that location for the fireweed flow.

The real issue as I see it when dealing with swarm deterrent methods, they come in two general forms. The first form involves an activity of some type that results in two colonies, lots of different ways of doing it, but they all boil down to some form of split, with many names to describe different ways of doing that split. The second form of swarm deterrent methods all revolve around ‘give them space’, and what a lot of new beekeepers fail to realize, ‘space’ does NOT mean fresh new frames of foundation, it means empty drawn comb where the bees have room to store nectar and/or raise brood. In particular in our area, we have a very strong honey flow during the swarmy part of the year, and the bees can bring in nectar FAR faster than they can build comb to store it, so we need to give them comb in the form of drawn supers to stay ahead of the incoming nectar. This is where your winter dead-outs turn into a godsend. A double deep that died out over the winter is a golden resource when late April and May roll around, it contains 20 frames of drawn comb that can be used to help deter swarming in the surviving hives.

I ran into one of the newer beekeeper club members in Canadian Tire a couple weeks ago, he went into the fall with 3 colonies, and one of them died over the winter. He was asking about purchasing a nuc in the spring. My response is, you don’t want a nuc to re-populate that hive, you want to keep those boxes of drawn comb in inventory, then when the swarmy part of the season arrives, you have the necessary resources on hand to manage your colonies. A winter deadout is the ticket to ‘give them space’ in May. Manage those two colonies to deter swarming with your boxes of drawn comb, then think about splits for increase AFTER the honey flow. Make your splits at the middle of June then manage them into the fall for increase by keeping the bees healthy and ensure they have food. Two strong colonies with a surplus of drawn comb in May and June will give you FAR more honey to harvest than 3 colonies that are always short of comb, those colonies will more likely give you a swarm instead of an extra box of honey.

If I look back at our records over the last few years, I have come to an important realization. Counting colonies is absolutely the wrong way to forecast your honey harvest. The correct way to forecast your honey harvest is to sit back in February and tally up how many supers of empty drawn comb you have to give the bees when the flow starts. Every box of comb we get drawn this year, translates directly to a box of full frames waiting for extractor next season after the honey flow. There is no instant gratification with beekeeping, this years work is about next years harvest. Our focus this year is less about increasing the colony count, and more about increasing the inventory of drawn supers to use for harvest in years going forward.

As we think thru the plans for this season with the bees, one thing is clear to me. Last years queens and comb, translate into this years harvest. When the overnight temperatures start up after May 15, we are already into the spring flow and the bees are starting to store the nectar that will be this years honey harvest. We can start putting cells into mating nucs after May 15, but that work is not about the harvest this year, it’s about preparing for the following year. What I find most interesting now as I sit down looking at the data, and planning our season with the bees, my focus has already shifted away from trying to plan what we will do about this years crop, my focus is now on what we want in terms of colony counts on stands by September, and how many empty drawn supers we can have in storage at that time. The honey crop this year, will be what it is, the groundwork for that was done last year thru the season. Our planning for this year is about how we can best prepare our bees and comb inventory for the next season. When we will raise queens, and when we will start new colonies for increase the topic we are now working out specifics for.

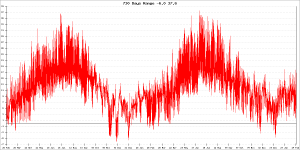

The graph is two years of temperature data here on the farm. Much like the hive scale, temperature is measured every 5 minutes and stored in a database from which we plot the graphs. Click on the graph to see a much larger version. I watched a show on one of the science oriented tv channels a couple years ago, and they had some very interesting insight. The show is called ‘orbit’, it’s a 4 part series where 2 young women travel around the world and show various major weather events that happen consistently year over year, then they proceed to explain why, it’s all to do with the tilt of the earth and our orbit around the sun, which in turn changes the amount of heating various parts of the earth get during various parts of the year. One of those ‘regularly scheduled’ events was fascinating, a waterfall in the northwest territories that freezes over. It’s a north flowing river, the fall is near Hay River, and the ice goes out in that fall in the same week every year. The reason for that, southern parts of the river start warming earlier in the season, and eventually the backlog of water is enough to start pushing the ice up to the fall, and it reaches a breaking point where you see a huge amount of ice give way and start cascading over that waterfall. As the days get longer in the south, there is more daytime heating, less night time cooling, and eventually that tipping point is reached. Timing of the ice letting go on the waterfall is driven by the length of day farther south, and it’s very consistent year over year.

We see a similar consistency here when I look at two years of temperature data collected on our property here at Rozehaven. Overnight low temps consistently dip down below 5C until we hit the 3rd week of May. But in around May 15, it’s like somebody hit the big light switch in the sky, and the overnight lows climb dramatically at that point. This becomes a very important time for using small splits as a swarm deterrent strategy. I like to use 2 or 3 frame splits for mating nucs when we start raising our replacement queens, but the data shows me, if I make those units up before May 15, they will have a high risk of chilling brood, which will set the nucs back so far they may not be viable anymore.

The other part of this equation then is the honey flows. Scale data shows us, to maximize our honey crop, we need maximum bee populations in the hives by May 1, and we want to keep those populations large thru the month of May and into June, without swarms coming out of the hives. This is the tricky part, because we are working against the bees natural instincts of trying to throw off a reproductive swarm during the spring flow. The easiest way to apply a strong swarm deterrent here on Vancouver Island, is to split hives in mid to late April, they have grown substantially by that time, and a split will set them back enough to deter swarming.

But, lets take a good hard look at the anatomy of the basic walk-away split and how that works in terms of timing for our honey flow. If we split a hive with a simple two box walk away split in late April, we end up with two halves. The donor half (box A) is now a single box, with a laying queen. They have roughly half the population and half the brood. Over the next 3 weeks that brood will all emerge, and the population will recover somewhat by mid May. The queenless half will start raising an emergency queen, and by mid May they will be in a situation of no brood left, it’s all emerged, with a queen just starting to lay. This is the time when our honey flow begins in earnest, so box A will have a reasonable, but not great population for producing honey, they will be capable of filling a super over the flow. In our second box, box B, 3 weeks after the split they have a freshly emerged queen, no brood, and a honey flow beginning. Over the next 3 weeks of flow, population is on the decline, and what bees are left need to be feeding brood, so we have less and less to forage during the heavy flow period. 3 weeks after the queen starts laying, they finally have brood emerging and the population has reached it’s low point and starting to recover, just in time for the honey flow to be tapering off. The end result of the exercise, one mediocre hive producing a box of honey, and one weak hive that will likely need support later in the season when it gets hot and dry. This ofc assumes all goes well in box A, and they just carry on after the split continuing to raise brood and expand the population. But that’s not been my experience in a walk away split. My experience is, the bees in the queenright half realize something drastic has happened, and proceed to do what bees do in that situation, they immediately start supercedure. There is a way to avoid the long and slow population decline in the queenless half of the walk away split, and that is to introduce a mated queen at the time of the split. But, if you look at the timing I mentioned above, in late April we will not have our own fresh queens to introduce, so, the only option is to purchase an imported queen for introduction into the queenless half of the split. If we do that, then both halves of the split will carry down the path mentioned above for box A, they both have a laying queen.

This is why I am not a fan of early splits as a swarm deterrent, the net result is two weaker colonies which will produce a small harvest at best, and in the worst case, no harvest at all from the spring flow we have at the lower elevations. Many of our club members have over time realized, the ‘no harvest at all’ case seems to be more predominant than the small harvest case when you use April splits as a swarm deterrent. This math changes dramatically if your focus for honey is targetting the later fireweed flow at higher elevations. If your target for honey is the fireweed, that split in April with a new introduced queen in the second half, should build well over the spring flow at lower elevations, and give you two strong hives to take up into the mountains chasing fireweed honey. That is a completely different strategy than we are using here, our target for honey flow it the spring flow here on our property. We dont have enough colonies to justify the work and expense of building an outyard in a logged patch full of fireweed. Instead, we participate in operation of a community yard set up by the local bee club, and just take a few of our colonies to that location for the fireweed flow.

The real issue as I see it when dealing with swarm deterrent methods, they come in two general forms. The first form involves an activity of some type that results in two colonies, lots of different ways of doing it, but they all boil down to some form of split, with many names to describe different ways of doing that split. The second form of swarm deterrent methods all revolve around ‘give them space’, and what a lot of new beekeepers fail to realize, ‘space’ does NOT mean fresh new frames of foundation, it means empty drawn comb where the bees have room to store nectar and/or raise brood. In particular in our area, we have a very strong honey flow during the swarmy part of the year, and the bees can bring in nectar FAR faster than they can build comb to store it, so we need to give them comb in the form of drawn supers to stay ahead of the incoming nectar. This is where your winter dead-outs turn into a godsend. A double deep that died out over the winter is a golden resource when late April and May roll around, it contains 20 frames of drawn comb that can be used to help deter swarming in the surviving hives.

I ran into one of the newer beekeeper club members in Canadian Tire a couple weeks ago, he went into the fall with 3 colonies, and one of them died over the winter. He was asking about purchasing a nuc in the spring. My response is, you don’t want a nuc to re-populate that hive, you want to keep those boxes of drawn comb in inventory, then when the swarmy part of the season arrives, you have the necessary resources on hand to manage your colonies. A winter deadout is the ticket to ‘give them space’ in May. Manage those two colonies to deter swarming with your boxes of drawn comb, then think about splits for increase AFTER the honey flow. Make your splits at the middle of June then manage them into the fall for increase by keeping the bees healthy and ensure they have food. Two strong colonies with a surplus of drawn comb in May and June will give you FAR more honey to harvest than 3 colonies that are always short of comb, those colonies will more likely give you a swarm instead of an extra box of honey.

If I look back at our records over the last few years, I have come to an important realization. Counting colonies is absolutely the wrong way to forecast your honey harvest. The correct way to forecast your honey harvest is to sit back in February and tally up how many supers of empty drawn comb you have to give the bees when the flow starts. Every box of comb we get drawn this year, translates directly to a box of full frames waiting for extractor next season after the honey flow. There is no instant gratification with beekeeping, this years work is about next years harvest. Our focus this year is less about increasing the colony count, and more about increasing the inventory of drawn supers to use for harvest in years going forward.

As we think thru the plans for this season with the bees, one thing is clear to me. Last years queens and comb, translate into this years harvest. When the overnight temperatures start up after May 15, we are already into the spring flow and the bees are starting to store the nectar that will be this years honey harvest. We can start putting cells into mating nucs after May 15, but that work is not about the harvest this year, it’s about preparing for the following year. What I find most interesting now as I sit down looking at the data, and planning our season with the bees, my focus has already shifted away from trying to plan what we will do about this years crop, my focus is now on what we want in terms of colony counts on stands by September, and how many empty drawn supers we can have in storage at that time. The honey crop this year, will be what it is, the groundwork for that was done last year thru the season. Our planning for this year is about how we can best prepare our bees and comb inventory for the next season. When we will raise queens, and when we will start new colonies for increase the topic we are now working out specifics for.

Planning the season

A small honey crop can easily be achieved in spite of how the bees are managed. It is what bees do, they gather nectar to produce honey, and they will do this no matter how the beekeeper manipulates the hives. The question then becomes, how to maximize nectar gathering for producing honey? If we want a large honey crop, we need to manage the bees to maximize the hive population at the time of the strongest flows. Two years of data from a hive on the scale show clearly the timeframes of interest, our flow runs runs roughly from the start of 2nd week of May, till the end of 2nd week of June. I dont think it’s a co-incidence, this is also the time when we hear of the most swarms. Last season, we first started hearing about swarms at the April bee club meeting, in the 4th week of April. Temperatures are another item we need to look at when thinking about managing the bees, if various forms of splits are part of the strategy, we cannot do smallish splits until overnight temperatures are suitable for a small cluster with brood.

The graph is two years of temperature data here on the farm. Much like the hive scale, temperature is measured every 5 minutes and stored in a database from which we plot the graphs. Click on the graph to see a much larger version. I watched a show on one of the science oriented tv channels a couple years ago, and they had some very interesting insight. The show is called ‘orbit’, it’s a 4 part series where 2 young women travel around the world and show various major weather events that happen consistently year over year, then they proceed to explain why, it’s all to do with the tilt of the earth and our orbit around the sun, which in turn changes the amount of heating various parts of the earth get during various parts of the year. One of those ‘regularly scheduled’ events was fascinating, a waterfall in the northwest territories that freezes over. It’s a north flowing river, the fall is near Hay River, and the ice goes out in that fall in the same week every year. The reason for that, southern parts of the river start warming earlier in the season, and eventually the backlog of water is enough to start pushing the ice up to the fall, and it reaches a breaking point where you see a huge amount of ice give way and start cascading over that waterfall. As the days get longer in the south, there is more daytime heating, less night time cooling, and eventually that tipping point is reached. Timing of the ice letting go on the waterfall is driven by the length of day farther south, and it’s very consistent year over year.

We see a similar consistency here when I look at two years of temperature data collected on our property here at Rozehaven. Overnight low temps consistently dip down below 5C until we hit the 3rd week of May. But in around May 15, it’s like somebody hit the big light switch in the sky, and the overnight lows climb dramatically at that point. This becomes a very important time for using small splits as a swarm deterrent strategy. I like to use 2 or 3 frame splits for mating nucs when we start raising our replacement queens, but the data shows me, if I make those units up before May 15, they will have a high risk of chilling brood, which will set the nucs back so far they may not be viable anymore.

The other part of this equation then is the honey flows. Scale data shows us, to maximize our honey crop, we need maximum bee populations in the hives by May 1, and we want to keep those populations large thru the month of May and into June, without swarms coming out of the hives. This is the tricky part, because we are working against the bees natural instincts of trying to throw off a reproductive swarm during the spring flow. The easiest way to apply a strong swarm deterrent here on Vancouver Island, is to split hives in mid to late April, they have grown substantially by that time, and a split will set them back enough to deter swarming.

But, lets take a good hard look at the anatomy of the basic walk-away split and how that works in terms of timing for our honey flow. If we split a hive with a simple two box walk away split in late April, we end up with two halves. The donor half (box A) is now a single box, with a laying queen. They have roughly half the population and half the brood. Over the next 3 weeks that brood will all emerge, and the population will recover somewhat by mid May. The queenless half will start raising an emergency queen, and by mid May they will be in a situation of no brood left, it’s all emerged, with a queen just starting to lay. This is the time when our honey flow begins in earnest, so box A will have a reasonable, but not great population for producing honey, they will be capable of filling a super over the flow. In our second box, box B, 3 weeks after the split they have a freshly emerged queen, no brood, and a honey flow beginning. Over the next 3 weeks of flow, population is on the decline, and what bees are left need to be feeding brood, so we have less and less to forage during the heavy flow period. 3 weeks after the queen starts laying, they finally have brood emerging and the population has reached it’s low point and starting to recover, just in time for the honey flow to be tapering off. The end result of the exercise, one mediocre hive producing a box of honey, and one weak hive that will likely need support later in the season when it gets hot and dry. This ofc assumes all goes well in box A, and they just carry on after the split continuing to raise brood and expand the population. But that’s not been my experience in a walk away split. My experience is, the bees in the queenright half realize something drastic has happened, and proceed to do what bees do in that situation, they immediately start supercedure. There is a way to avoid the long and slow population decline in the queenless half of the walk away split, and that is to introduce a mated queen at the time of the split. But, if you look at the timing I mentioned above, in late April we will not have our own fresh queens to introduce, so, the only option is to purchase an imported queen for introduction into the queenless half of the split. If we do that, then both halves of the split will carry down the path mentioned above for box A, they both have a laying queen.

This is why I am not a fan of early splits as a swarm deterrent, the net result is two weaker colonies which will produce a small harvest at best, and in the worst case, no harvest at all from the spring flow we have at the lower elevations. Many of our club members have over time realized, the ‘no harvest at all’ case seems to be more predominant than the small harvest case when you use April splits as a swarm deterrent. This math changes dramatically if your focus for honey is targetting the later fireweed flow at higher elevations. If your target for honey is the fireweed, that split in April with a new introduced queen in the second half, should build well over the spring flow at lower elevations, and give you two strong hives to take up into the mountains chasing fireweed honey. That is a completely different strategy than we are using here, our target for honey flow it the spring flow here on our property. We dont have enough colonies to justify the work and expense of building an outyard in a logged patch full of fireweed. Instead, we participate in operation of a community yard set up by the local bee club, and just take a few of our colonies to that location for the fireweed flow.

The real issue as I see it when dealing with swarm deterrent methods, they come in two general forms. The first form involves an activity of some type that results in two colonies, lots of different ways of doing it, but they all boil down to some form of split, with many names to describe different ways of doing that split. The second form of swarm deterrent methods all revolve around ‘give them space’, and what a lot of new beekeepers fail to realize, ‘space’ does NOT mean fresh new frames of foundation, it means empty drawn comb where the bees have room to store nectar and/or raise brood. In particular in our area, we have a very strong honey flow during the swarmy part of the year, and the bees can bring in nectar FAR faster than they can build comb to store it, so we need to give them comb in the form of drawn supers to stay ahead of the incoming nectar. This is where your winter dead-outs turn into a godsend. A double deep that died out over the winter is a golden resource when late April and May roll around, it contains 20 frames of drawn comb that can be used to help deter swarming in the surviving hives.

I ran into one of the newer beekeeper club members in Canadian Tire a couple weeks ago, he went into the fall with 3 colonies, and one of them died over the winter. He was asking about purchasing a nuc in the spring. My response is, you don’t want a nuc to re-populate that hive, you want to keep those boxes of drawn comb in inventory, then when the swarmy part of the season arrives, you have the necessary resources on hand to manage your colonies. A winter deadout is the ticket to ‘give them space’ in May. Manage those two colonies to deter swarming with your boxes of drawn comb, then think about splits for increase AFTER the honey flow. Make your splits at the middle of June then manage them into the fall for increase by keeping the bees healthy and ensure they have food. Two strong colonies with a surplus of drawn comb in May and June will give you FAR more honey to harvest than 3 colonies that are always short of comb, those colonies will more likely give you a swarm instead of an extra box of honey.

If I look back at our records over the last few years, I have come to an important realization. Counting colonies is absolutely the wrong way to forecast your honey harvest. The correct way to forecast your honey harvest is to sit back in February and tally up how many supers of empty drawn comb you have to give the bees when the flow starts. Every box of comb we get drawn this year, translates directly to a box of full frames waiting for extractor next season after the honey flow. There is no instant gratification with beekeeping, this years work is about next years harvest. Our focus this year is less about increasing the colony count, and more about increasing the inventory of drawn supers to use for harvest in years going forward.

As we think thru the plans for this season with the bees, one thing is clear to me. Last years queens and comb, translate into this years harvest. When the overnight temperatures start up after May 15, we are already into the spring flow and the bees are starting to store the nectar that will be this years honey harvest. We can start putting cells into mating nucs after May 15, but that work is not about the harvest this year, it’s about preparing for the following year. What I find most interesting now as I sit down looking at the data, and planning our season with the bees, my focus has already shifted away from trying to plan what we will do about this years crop, my focus is now on what we want in terms of colony counts on stands by September, and how many empty drawn supers we can have in storage at that time. The honey crop this year, will be what it is, the groundwork for that was done last year thru the season. Our planning for this year is about how we can best prepare our bees and comb inventory for the next season. When we will raise queens, and when we will start new colonies for increase the topic we are now working out specifics for.

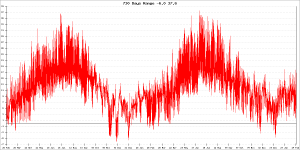

The graph is two years of temperature data here on the farm. Much like the hive scale, temperature is measured every 5 minutes and stored in a database from which we plot the graphs. Click on the graph to see a much larger version. I watched a show on one of the science oriented tv channels a couple years ago, and they had some very interesting insight. The show is called ‘orbit’, it’s a 4 part series where 2 young women travel around the world and show various major weather events that happen consistently year over year, then they proceed to explain why, it’s all to do with the tilt of the earth and our orbit around the sun, which in turn changes the amount of heating various parts of the earth get during various parts of the year. One of those ‘regularly scheduled’ events was fascinating, a waterfall in the northwest territories that freezes over. It’s a north flowing river, the fall is near Hay River, and the ice goes out in that fall in the same week every year. The reason for that, southern parts of the river start warming earlier in the season, and eventually the backlog of water is enough to start pushing the ice up to the fall, and it reaches a breaking point where you see a huge amount of ice give way and start cascading over that waterfall. As the days get longer in the south, there is more daytime heating, less night time cooling, and eventually that tipping point is reached. Timing of the ice letting go on the waterfall is driven by the length of day farther south, and it’s very consistent year over year.

We see a similar consistency here when I look at two years of temperature data collected on our property here at Rozehaven. Overnight low temps consistently dip down below 5C until we hit the 3rd week of May. But in around May 15, it’s like somebody hit the big light switch in the sky, and the overnight lows climb dramatically at that point. This becomes a very important time for using small splits as a swarm deterrent strategy. I like to use 2 or 3 frame splits for mating nucs when we start raising our replacement queens, but the data shows me, if I make those units up before May 15, they will have a high risk of chilling brood, which will set the nucs back so far they may not be viable anymore.

The other part of this equation then is the honey flows. Scale data shows us, to maximize our honey crop, we need maximum bee populations in the hives by May 1, and we want to keep those populations large thru the month of May and into June, without swarms coming out of the hives. This is the tricky part, because we are working against the bees natural instincts of trying to throw off a reproductive swarm during the spring flow. The easiest way to apply a strong swarm deterrent here on Vancouver Island, is to split hives in mid to late April, they have grown substantially by that time, and a split will set them back enough to deter swarming.

But, lets take a good hard look at the anatomy of the basic walk-away split and how that works in terms of timing for our honey flow. If we split a hive with a simple two box walk away split in late April, we end up with two halves. The donor half (box A) is now a single box, with a laying queen. They have roughly half the population and half the brood. Over the next 3 weeks that brood will all emerge, and the population will recover somewhat by mid May. The queenless half will start raising an emergency queen, and by mid May they will be in a situation of no brood left, it’s all emerged, with a queen just starting to lay. This is the time when our honey flow begins in earnest, so box A will have a reasonable, but not great population for producing honey, they will be capable of filling a super over the flow. In our second box, box B, 3 weeks after the split they have a freshly emerged queen, no brood, and a honey flow beginning. Over the next 3 weeks of flow, population is on the decline, and what bees are left need to be feeding brood, so we have less and less to forage during the heavy flow period. 3 weeks after the queen starts laying, they finally have brood emerging and the population has reached it’s low point and starting to recover, just in time for the honey flow to be tapering off. The end result of the exercise, one mediocre hive producing a box of honey, and one weak hive that will likely need support later in the season when it gets hot and dry. This ofc assumes all goes well in box A, and they just carry on after the split continuing to raise brood and expand the population. But that’s not been my experience in a walk away split. My experience is, the bees in the queenright half realize something drastic has happened, and proceed to do what bees do in that situation, they immediately start supercedure. There is a way to avoid the long and slow population decline in the queenless half of the walk away split, and that is to introduce a mated queen at the time of the split. But, if you look at the timing I mentioned above, in late April we will not have our own fresh queens to introduce, so, the only option is to purchase an imported queen for introduction into the queenless half of the split. If we do that, then both halves of the split will carry down the path mentioned above for box A, they both have a laying queen.

This is why I am not a fan of early splits as a swarm deterrent, the net result is two weaker colonies which will produce a small harvest at best, and in the worst case, no harvest at all from the spring flow we have at the lower elevations. Many of our club members have over time realized, the ‘no harvest at all’ case seems to be more predominant than the small harvest case when you use April splits as a swarm deterrent. This math changes dramatically if your focus for honey is targetting the later fireweed flow at higher elevations. If your target for honey is the fireweed, that split in April with a new introduced queen in the second half, should build well over the spring flow at lower elevations, and give you two strong hives to take up into the mountains chasing fireweed honey. That is a completely different strategy than we are using here, our target for honey flow it the spring flow here on our property. We dont have enough colonies to justify the work and expense of building an outyard in a logged patch full of fireweed. Instead, we participate in operation of a community yard set up by the local bee club, and just take a few of our colonies to that location for the fireweed flow.

The real issue as I see it when dealing with swarm deterrent methods, they come in two general forms. The first form involves an activity of some type that results in two colonies, lots of different ways of doing it, but they all boil down to some form of split, with many names to describe different ways of doing that split. The second form of swarm deterrent methods all revolve around ‘give them space’, and what a lot of new beekeepers fail to realize, ‘space’ does NOT mean fresh new frames of foundation, it means empty drawn comb where the bees have room to store nectar and/or raise brood. In particular in our area, we have a very strong honey flow during the swarmy part of the year, and the bees can bring in nectar FAR faster than they can build comb to store it, so we need to give them comb in the form of drawn supers to stay ahead of the incoming nectar. This is where your winter dead-outs turn into a godsend. A double deep that died out over the winter is a golden resource when late April and May roll around, it contains 20 frames of drawn comb that can be used to help deter swarming in the surviving hives.

I ran into one of the newer beekeeper club members in Canadian Tire a couple weeks ago, he went into the fall with 3 colonies, and one of them died over the winter. He was asking about purchasing a nuc in the spring. My response is, you don’t want a nuc to re-populate that hive, you want to keep those boxes of drawn comb in inventory, then when the swarmy part of the season arrives, you have the necessary resources on hand to manage your colonies. A winter deadout is the ticket to ‘give them space’ in May. Manage those two colonies to deter swarming with your boxes of drawn comb, then think about splits for increase AFTER the honey flow. Make your splits at the middle of June then manage them into the fall for increase by keeping the bees healthy and ensure they have food. Two strong colonies with a surplus of drawn comb in May and June will give you FAR more honey to harvest than 3 colonies that are always short of comb, those colonies will more likely give you a swarm instead of an extra box of honey.

If I look back at our records over the last few years, I have come to an important realization. Counting colonies is absolutely the wrong way to forecast your honey harvest. The correct way to forecast your honey harvest is to sit back in February and tally up how many supers of empty drawn comb you have to give the bees when the flow starts. Every box of comb we get drawn this year, translates directly to a box of full frames waiting for extractor next season after the honey flow. There is no instant gratification with beekeeping, this years work is about next years harvest. Our focus this year is less about increasing the colony count, and more about increasing the inventory of drawn supers to use for harvest in years going forward.

As we think thru the plans for this season with the bees, one thing is clear to me. Last years queens and comb, translate into this years harvest. When the overnight temperatures start up after May 15, we are already into the spring flow and the bees are starting to store the nectar that will be this years honey harvest. We can start putting cells into mating nucs after May 15, but that work is not about the harvest this year, it’s about preparing for the following year. What I find most interesting now as I sit down looking at the data, and planning our season with the bees, my focus has already shifted away from trying to plan what we will do about this years crop, my focus is now on what we want in terms of colony counts on stands by September, and how many empty drawn supers we can have in storage at that time. The honey crop this year, will be what it is, the groundwork for that was done last year thru the season. Our planning for this year is about how we can best prepare our bees and comb inventory for the next season. When we will raise queens, and when we will start new colonies for increase the topic we are now working out specifics for.

The graph is two years of temperature data here on the farm. Much like the hive scale, temperature is measured every 5 minutes and stored in a database from which we plot the graphs. Click on the graph to see a much larger version. I watched a show on one of the science oriented tv channels a couple years ago, and they had some very interesting insight. The show is called ‘orbit’, it’s a 4 part series where 2 young women travel around the world and show various major weather events that happen consistently year over year, then they proceed to explain why, it’s all to do with the tilt of the earth and our orbit around the sun, which in turn changes the amount of heating various parts of the earth get during various parts of the year. One of those ‘regularly scheduled’ events was fascinating, a waterfall in the northwest territories that freezes over. It’s a north flowing river, the fall is near Hay River, and the ice goes out in that fall in the same week every year. The reason for that, southern parts of the river start warming earlier in the season, and eventually the backlog of water is enough to start pushing the ice up to the fall, and it reaches a breaking point where you see a huge amount of ice give way and start cascading over that waterfall. As the days get longer in the south, there is more daytime heating, less night time cooling, and eventually that tipping point is reached. Timing of the ice letting go on the waterfall is driven by the length of day farther south, and it’s very consistent year over year.

We see a similar consistency here when I look at two years of temperature data collected on our property here at Rozehaven. Overnight low temps consistently dip down below 5C until we hit the 3rd week of May. But in around May 15, it’s like somebody hit the big light switch in the sky, and the overnight lows climb dramatically at that point. This becomes a very important time for using small splits as a swarm deterrent strategy. I like to use 2 or 3 frame splits for mating nucs when we start raising our replacement queens, but the data shows me, if I make those units up before May 15, they will have a high risk of chilling brood, which will set the nucs back so far they may not be viable anymore.

The other part of this equation then is the honey flows. Scale data shows us, to maximize our honey crop, we need maximum bee populations in the hives by May 1, and we want to keep those populations large thru the month of May and into June, without swarms coming out of the hives. This is the tricky part, because we are working against the bees natural instincts of trying to throw off a reproductive swarm during the spring flow. The easiest way to apply a strong swarm deterrent here on Vancouver Island, is to split hives in mid to late April, they have grown substantially by that time, and a split will set them back enough to deter swarming.

But, lets take a good hard look at the anatomy of the basic walk-away split and how that works in terms of timing for our honey flow. If we split a hive with a simple two box walk away split in late April, we end up with two halves. The donor half (box A) is now a single box, with a laying queen. They have roughly half the population and half the brood. Over the next 3 weeks that brood will all emerge, and the population will recover somewhat by mid May. The queenless half will start raising an emergency queen, and by mid May they will be in a situation of no brood left, it’s all emerged, with a queen just starting to lay. This is the time when our honey flow begins in earnest, so box A will have a reasonable, but not great population for producing honey, they will be capable of filling a super over the flow. In our second box, box B, 3 weeks after the split they have a freshly emerged queen, no brood, and a honey flow beginning. Over the next 3 weeks of flow, population is on the decline, and what bees are left need to be feeding brood, so we have less and less to forage during the heavy flow period. 3 weeks after the queen starts laying, they finally have brood emerging and the population has reached it’s low point and starting to recover, just in time for the honey flow to be tapering off. The end result of the exercise, one mediocre hive producing a box of honey, and one weak hive that will likely need support later in the season when it gets hot and dry. This ofc assumes all goes well in box A, and they just carry on after the split continuing to raise brood and expand the population. But that’s not been my experience in a walk away split. My experience is, the bees in the queenright half realize something drastic has happened, and proceed to do what bees do in that situation, they immediately start supercedure. There is a way to avoid the long and slow population decline in the queenless half of the walk away split, and that is to introduce a mated queen at the time of the split. But, if you look at the timing I mentioned above, in late April we will not have our own fresh queens to introduce, so, the only option is to purchase an imported queen for introduction into the queenless half of the split. If we do that, then both halves of the split will carry down the path mentioned above for box A, they both have a laying queen.

This is why I am not a fan of early splits as a swarm deterrent, the net result is two weaker colonies which will produce a small harvest at best, and in the worst case, no harvest at all from the spring flow we have at the lower elevations. Many of our club members have over time realized, the ‘no harvest at all’ case seems to be more predominant than the small harvest case when you use April splits as a swarm deterrent. This math changes dramatically if your focus for honey is targetting the later fireweed flow at higher elevations. If your target for honey is the fireweed, that split in April with a new introduced queen in the second half, should build well over the spring flow at lower elevations, and give you two strong hives to take up into the mountains chasing fireweed honey. That is a completely different strategy than we are using here, our target for honey flow it the spring flow here on our property. We dont have enough colonies to justify the work and expense of building an outyard in a logged patch full of fireweed. Instead, we participate in operation of a community yard set up by the local bee club, and just take a few of our colonies to that location for the fireweed flow.

The real issue as I see it when dealing with swarm deterrent methods, they come in two general forms. The first form involves an activity of some type that results in two colonies, lots of different ways of doing it, but they all boil down to some form of split, with many names to describe different ways of doing that split. The second form of swarm deterrent methods all revolve around ‘give them space’, and what a lot of new beekeepers fail to realize, ‘space’ does NOT mean fresh new frames of foundation, it means empty drawn comb where the bees have room to store nectar and/or raise brood. In particular in our area, we have a very strong honey flow during the swarmy part of the year, and the bees can bring in nectar FAR faster than they can build comb to store it, so we need to give them comb in the form of drawn supers to stay ahead of the incoming nectar. This is where your winter dead-outs turn into a godsend. A double deep that died out over the winter is a golden resource when late April and May roll around, it contains 20 frames of drawn comb that can be used to help deter swarming in the surviving hives.

I ran into one of the newer beekeeper club members in Canadian Tire a couple weeks ago, he went into the fall with 3 colonies, and one of them died over the winter. He was asking about purchasing a nuc in the spring. My response is, you don’t want a nuc to re-populate that hive, you want to keep those boxes of drawn comb in inventory, then when the swarmy part of the season arrives, you have the necessary resources on hand to manage your colonies. A winter deadout is the ticket to ‘give them space’ in May. Manage those two colonies to deter swarming with your boxes of drawn comb, then think about splits for increase AFTER the honey flow. Make your splits at the middle of June then manage them into the fall for increase by keeping the bees healthy and ensure they have food. Two strong colonies with a surplus of drawn comb in May and June will give you FAR more honey to harvest than 3 colonies that are always short of comb, those colonies will more likely give you a swarm instead of an extra box of honey.

If I look back at our records over the last few years, I have come to an important realization. Counting colonies is absolutely the wrong way to forecast your honey harvest. The correct way to forecast your honey harvest is to sit back in February and tally up how many supers of empty drawn comb you have to give the bees when the flow starts. Every box of comb we get drawn this year, translates directly to a box of full frames waiting for extractor next season after the honey flow. There is no instant gratification with beekeeping, this years work is about next years harvest. Our focus this year is less about increasing the colony count, and more about increasing the inventory of drawn supers to use for harvest in years going forward.

As we think thru the plans for this season with the bees, one thing is clear to me. Last years queens and comb, translate into this years harvest. When the overnight temperatures start up after May 15, we are already into the spring flow and the bees are starting to store the nectar that will be this years honey harvest. We can start putting cells into mating nucs after May 15, but that work is not about the harvest this year, it’s about preparing for the following year. What I find most interesting now as I sit down looking at the data, and planning our season with the bees, my focus has already shifted away from trying to plan what we will do about this years crop, my focus is now on what we want in terms of colony counts on stands by September, and how many empty drawn supers we can have in storage at that time. The honey crop this year, will be what it is, the groundwork for that was done last year thru the season. Our planning for this year is about how we can best prepare our bees and comb inventory for the next season. When we will raise queens, and when we will start new colonies for increase the topic we are now working out specifics for.

The graph is two years of temperature data here on the farm. Much like the hive scale, temperature is measured every 5 minutes and stored in a database from which we plot the graphs. Click on the graph to see a much larger version. I watched a show on one of the science oriented tv channels a couple years ago, and they had some very interesting insight. The show is called ‘orbit’, it’s a 4 part series where 2 young women travel around the world and show various major weather events that happen consistently year over year, then they proceed to explain why, it’s all to do with the tilt of the earth and our orbit around the sun, which in turn changes the amount of heating various parts of the earth get during various parts of the year. One of those ‘regularly scheduled’ events was fascinating, a waterfall in the northwest territories that freezes over. It’s a north flowing river, the fall is near Hay River, and the ice goes out in that fall in the same week every year. The reason for that, southern parts of the river start warming earlier in the season, and eventually the backlog of water is enough to start pushing the ice up to the fall, and it reaches a breaking point where you see a huge amount of ice give way and start cascading over that waterfall. As the days get longer in the south, there is more daytime heating, less night time cooling, and eventually that tipping point is reached. Timing of the ice letting go on the waterfall is driven by the length of day farther south, and it’s very consistent year over year.

We see a similar consistency here when I look at two years of temperature data collected on our property here at Rozehaven. Overnight low temps consistently dip down below 5C until we hit the 3rd week of May. But in around May 15, it’s like somebody hit the big light switch in the sky, and the overnight lows climb dramatically at that point. This becomes a very important time for using small splits as a swarm deterrent strategy. I like to use 2 or 3 frame splits for mating nucs when we start raising our replacement queens, but the data shows me, if I make those units up before May 15, they will have a high risk of chilling brood, which will set the nucs back so far they may not be viable anymore.

The other part of this equation then is the honey flows. Scale data shows us, to maximize our honey crop, we need maximum bee populations in the hives by May 1, and we want to keep those populations large thru the month of May and into June, without swarms coming out of the hives. This is the tricky part, because we are working against the bees natural instincts of trying to throw off a reproductive swarm during the spring flow. The easiest way to apply a strong swarm deterrent here on Vancouver Island, is to split hives in mid to late April, they have grown substantially by that time, and a split will set them back enough to deter swarming.

But, lets take a good hard look at the anatomy of the basic walk-away split and how that works in terms of timing for our honey flow. If we split a hive with a simple two box walk away split in late April, we end up with two halves. The donor half (box A) is now a single box, with a laying queen. They have roughly half the population and half the brood. Over the next 3 weeks that brood will all emerge, and the population will recover somewhat by mid May. The queenless half will start raising an emergency queen, and by mid May they will be in a situation of no brood left, it’s all emerged, with a queen just starting to lay. This is the time when our honey flow begins in earnest, so box A will have a reasonable, but not great population for producing honey, they will be capable of filling a super over the flow. In our second box, box B, 3 weeks after the split they have a freshly emerged queen, no brood, and a honey flow beginning. Over the next 3 weeks of flow, population is on the decline, and what bees are left need to be feeding brood, so we have less and less to forage during the heavy flow period. 3 weeks after the queen starts laying, they finally have brood emerging and the population has reached it’s low point and starting to recover, just in time for the honey flow to be tapering off. The end result of the exercise, one mediocre hive producing a box of honey, and one weak hive that will likely need support later in the season when it gets hot and dry. This ofc assumes all goes well in box A, and they just carry on after the split continuing to raise brood and expand the population. But that’s not been my experience in a walk away split. My experience is, the bees in the queenright half realize something drastic has happened, and proceed to do what bees do in that situation, they immediately start supercedure. There is a way to avoid the long and slow population decline in the queenless half of the walk away split, and that is to introduce a mated queen at the time of the split. But, if you look at the timing I mentioned above, in late April we will not have our own fresh queens to introduce, so, the only option is to purchase an imported queen for introduction into the queenless half of the split. If we do that, then both halves of the split will carry down the path mentioned above for box A, they both have a laying queen.

This is why I am not a fan of early splits as a swarm deterrent, the net result is two weaker colonies which will produce a small harvest at best, and in the worst case, no harvest at all from the spring flow we have at the lower elevations. Many of our club members have over time realized, the ‘no harvest at all’ case seems to be more predominant than the small harvest case when you use April splits as a swarm deterrent. This math changes dramatically if your focus for honey is targetting the later fireweed flow at higher elevations. If your target for honey is the fireweed, that split in April with a new introduced queen in the second half, should build well over the spring flow at lower elevations, and give you two strong hives to take up into the mountains chasing fireweed honey. That is a completely different strategy than we are using here, our target for honey flow it the spring flow here on our property. We dont have enough colonies to justify the work and expense of building an outyard in a logged patch full of fireweed. Instead, we participate in operation of a community yard set up by the local bee club, and just take a few of our colonies to that location for the fireweed flow.

The real issue as I see it when dealing with swarm deterrent methods, they come in two general forms. The first form involves an activity of some type that results in two colonies, lots of different ways of doing it, but they all boil down to some form of split, with many names to describe different ways of doing that split. The second form of swarm deterrent methods all revolve around ‘give them space’, and what a lot of new beekeepers fail to realize, ‘space’ does NOT mean fresh new frames of foundation, it means empty drawn comb where the bees have room to store nectar and/or raise brood. In particular in our area, we have a very strong honey flow during the swarmy part of the year, and the bees can bring in nectar FAR faster than they can build comb to store it, so we need to give them comb in the form of drawn supers to stay ahead of the incoming nectar. This is where your winter dead-outs turn into a godsend. A double deep that died out over the winter is a golden resource when late April and May roll around, it contains 20 frames of drawn comb that can be used to help deter swarming in the surviving hives.

I ran into one of the newer beekeeper club members in Canadian Tire a couple weeks ago, he went into the fall with 3 colonies, and one of them died over the winter. He was asking about purchasing a nuc in the spring. My response is, you don’t want a nuc to re-populate that hive, you want to keep those boxes of drawn comb in inventory, then when the swarmy part of the season arrives, you have the necessary resources on hand to manage your colonies. A winter deadout is the ticket to ‘give them space’ in May. Manage those two colonies to deter swarming with your boxes of drawn comb, then think about splits for increase AFTER the honey flow. Make your splits at the middle of June then manage them into the fall for increase by keeping the bees healthy and ensure they have food. Two strong colonies with a surplus of drawn comb in May and June will give you FAR more honey to harvest than 3 colonies that are always short of comb, those colonies will more likely give you a swarm instead of an extra box of honey.

If I look back at our records over the last few years, I have come to an important realization. Counting colonies is absolutely the wrong way to forecast your honey harvest. The correct way to forecast your honey harvest is to sit back in February and tally up how many supers of empty drawn comb you have to give the bees when the flow starts. Every box of comb we get drawn this year, translates directly to a box of full frames waiting for extractor next season after the honey flow. There is no instant gratification with beekeeping, this years work is about next years harvest. Our focus this year is less about increasing the colony count, and more about increasing the inventory of drawn supers to use for harvest in years going forward.

As we think thru the plans for this season with the bees, one thing is clear to me. Last years queens and comb, translate into this years harvest. When the overnight temperatures start up after May 15, we are already into the spring flow and the bees are starting to store the nectar that will be this years honey harvest. We can start putting cells into mating nucs after May 15, but that work is not about the harvest this year, it’s about preparing for the following year. What I find most interesting now as I sit down looking at the data, and planning our season with the bees, my focus has already shifted away from trying to plan what we will do about this years crop, my focus is now on what we want in terms of colony counts on stands by September, and how many empty drawn supers we can have in storage at that time. The honey crop this year, will be what it is, the groundwork for that was done last year thru the season. Our planning for this year is about how we can best prepare our bees and comb inventory for the next season. When we will raise queens, and when we will start new colonies for increase the topic we are now working out specifics for.